Search

A 2005 Interview by Leanna Chamish

Leanna: Kim, have you have worked with both film and video? If so, which do you prefer to work with, and why? What are the pros and cons of both mediums?

Kim: It would be difficult for me to comment on working with film as far as motion pictures are concerned since I’ve only worked with film as a STILL photographer. However, I do understand in both theoretical and practical ways how the two mediums differ. If I had my choice, i.e. $$$, I would choose film. It’s a more expressive medium in that it captures much more information than video is able to, i.e. shadow detail, texture, color saturation, resolution, etc.

I think video’s strong points are its economy. It allows me as a director to discount $$$ as I might have to do if I were counting the number of feet of film that I was burning through and to focus more on the performance of the actors, the lighting and mood of the scene, the movement of the camera and the overall impact of the scene.

Leanna: What kind of affordable film or video camera would you recommend to those in the independent film business? What are the pluses and features on these cameras?

Kim: I’m looking at the new DV cameras that feature adjustable frame rates such as the 24p Panasonic camcorders. I believe that DV is the most affordable avenue for up and coming filmmakers to get their stories on tape.

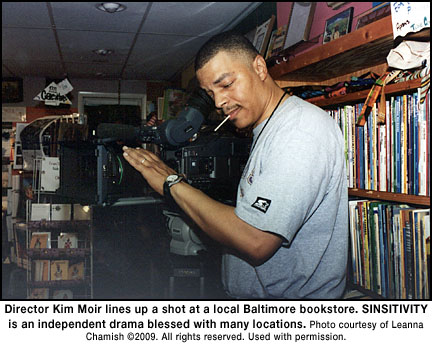

Leanna: What camera and format did you use to shoot Sinsitivity?

Kim: For “Sinsitivity,” I used the DVW – 790. It’s a digital Betacam format camera used for professional broadcast applications. Its image quality is excellent and is surpassed only by HD and film. Its drawback is it’s size, nearly 30 lbs with battery and it’s expense. I could only afford to rent it occasionally.

Leanna: What kind of lighting equipment do you use? What do you feel is essential as a basic kit for someone starting out in this business?

Kim: An essential lighting kit in my opinion should include some kind of Chimera or soft light along with a variety of flag and patterns to help create mood. You should also have a variety of low wattage, high impact instruments to paint a background and to backlight subjects with. I like Dedo lights that have their own adjustable ballast, but they’re rumored to expensive. What ever light is used, it’s essentially that it be controllable — both in it’s intensity with a dimmer and scrims and gels, but that it have good barn doors or flags to control where the light can and cannot go.

Leanna: Or did you depend on your lighting guys (like John Miyagawa) to bring the lighting equipment)

Kim: For “Sinsitivity” I did depend on John Miyagawa and Kwame’ Bey a great deal. I basically described the scene to them and allowed them to create the lighting and mood. I made comments when I thought the lighting didn’t convey the mood of the script, but those occasions were very few. Both are talented lighting designers with their own strengths and interests. John brought many of his own instruments which were supplemented with what we could rent. Kwame’ worked creatively with what we were able to rent.

Leanna: If you have worked with partners in the past, what are pros and cons to this collaborative? Could you talk some about working with Deborah, especially since she is your wife?

Kim: I have wanted to work with a collaborator in the past to diminish some of the workload, but never found anyone who wanted to work with me, or who I felt comfortable working with. Many of the folks who’d be most qualified to work with me are pursuing their own projects. Others would require too much coaching and supervision on my part and it would be almost easier in those situations to do it myself.

The pros of working with a collaborator, in my opinion, would include having someone who you could bounce ideas off of, someone who could share the responsibility of producing the film. When I began “Sinsitivity” I didn’t have a producer other than myself. As the production moved forward, my wife began to assume those responsibilities.

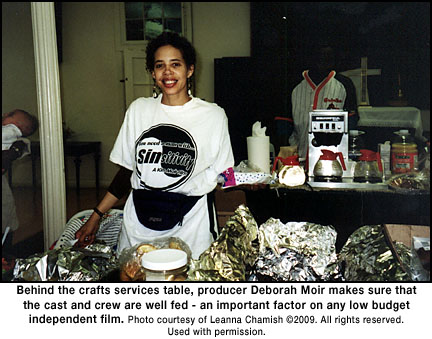

Working with Deb came about almost by accident. Initially, I don’t think she wanted anything to do with the project. I think she thought it was gonna be a T & A fest. Once she read the script, she knew I was into something deeper and more meaningful. Her participation grew over time in response to the challenges I was facing as the production geared up. Because there was no one who really appealed to me or who stepped up as a collaborator, I was wearing all of the hats. At certain points things began to overwhelm me and Deb stepped in and picked up some slack. She initially began her involvement by catering for the cast and crew. On another day she’d supplement that work by acting as script supervisor, the next she’d be involved with securing locations.

Frankly, she was one of the few people I could trust to follow through on their responsibilities without having their hands out for money that I didn’t have. There were others; R.T. Leftwich, David Wainwright, Terry Williams, Vic Blandburg and Leanna Chamish and they became the core of my crew. Others helped out when their full time jobs and family obligations allowed them to. Most, if not all of these people worked for no money because they believed in me, the project and wanted the opportunity to work on films. It was the first opportunity for many of us.

Leanna: What kind of pre-planning do you do for an upcoming film? Do you storyboard? Do you hold script meetings to get feedback on what will and will not work?

Kim: Our pre-production for “Sinsitivity” was comprised of a meeting with the various department heads — lighting, sound, makeup. During those meetings I gave out scripts to everyone and explained to them what I was trying to accomplish and how I saw the project coming together. I got feedback from everyone involved and incorporated that into our shooting plan and schedule. Our schedule worked well for the first two weeks of production mainly due to the fact that we had a loaner camera. We had to get as much of the film shot while we had access to that camera.

I didn’t get to storyboard although I’ve done more research on it and will include it in my pre-production planning for future projects. It assists in many aspects of the production including lighting, blocking and set design. It wasn’t readily available to me for “Sinsitivity,” but I’ll seek it out next time around.

We did rehearse for about two weeks and they were fairly rigorous. During those rehearsals, we dealt with the actors and their character interpretations and blocking mainly. I used a camcorder to begin visualizing how a scene might look during the actual production. That turned out to be a good move. I studied that footage before we began production, so when we actually began shooting, it’s like I was seeing these shots for the second time which made it easier to identify what did and didn’t work.

Leanna: Are your productions self-financed, or do you have investors? If you have investors, what is your advice on how to obtain them?

Kim: For “Sinsitivity”, I happened to have had two small investors who came on board after principle photography was underway. Frankly, they’re great people who were far more interested in seeing me get the movie made than seeing any windfall dollars on the back end. I pitched the idea to scores of people — some of whom were very well heeled, but who opted not to get involved. For that reason, I’m not sure what kind of advice I could offer given that my average for success was pretty bad. Most “experts” recommend focusing your attention on doctors, lawyers, real estate developers and other “high income” individuals. This probably makes sense. I spent as much time selling $15.00 tee shirts and caps to individuals as I did getting one of my “big money” investors, so the amount of time spent and the end result might point towards going after those whose incomes make them more likely to be able to fund a motion picture.

Leanna: What, of all your projects, has had the largest budget? Which has had the smallest budget? Can you give me examples of where the money goes on a project? Can you give me cost reasons of why one film is more expensive than the other?

Kim: “Sinsitivity” is the only project I’ve ever produced using any real money obtained from other people. Our prime expenditures were in equipment rentals and tape stock, although we also spent a lot on food. We also spent on some wardrobe items, location expenses, etc.

Leanna: Is there script-writing or script-formatting software out that you recommend using?

Kim: I use Scriptware personally. It does the job of formatting that I require — in addition it serves as thesaurus and spell checker. Although in the time since I purchased it, other more integrated software packages have been released- these packages promise to interface with other filmmaking software packages such as budgeting and scheduling.

Leanna: Who comes up with the story and the script? Is it a collaborative effort?

Kim: One of the reasons that I got involved with indie filmmaking was to fill in the gap that I believe exists for intelligent stories about African Americans. I have a number of story ideas. At this point, I don’t need any assistance with story ideas or writing scripts, but I don’t rule out either in the future.

Leanna: Kim, how do you go about holding auditions for a new project? How do you get the word out? Where do you hold the auditions? Do you have any sort of form for the actors to initially fill out at the audition? Do you video tape the auditions? Do you allow actors to send in video taped auditions with their resumes?

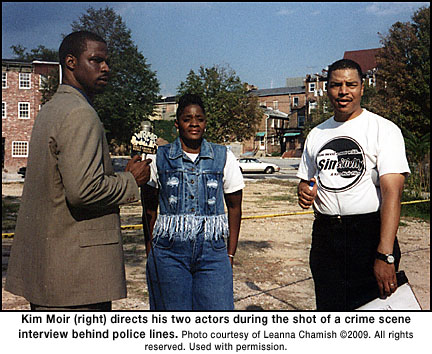

Kim: For casting of “Sinsitivity”, we cast in the Baltimore/D.C. area. We used local media, film commission hotlines and word of mouth to solicit actors. We had approx. 125 actors respond to the auditions. We did videotape auditions and did not solicit or accept videotapes from actors who did not show up personally to audition.

Leanna: What are the advantages and disadvantages of working with union or non-union actors?

Kim: The main advantage was not having to deal with an additional layer of bureaucracy. Indie films frequently have to work quickly just to be produced. Anything that can draw out the process of principle photography can potentially scuttle the entire film. We found very talented and capable actors and actresses outside of the union umbrella. I would like to work with union actors/actresses in the future when my budgets will support it.

Leanna: Do you feel it is important to get together with the cast and crew before shooting officially commences to go over the film, the plot, the duties of the individuals, and conduct and etiquette on the set?

Kim: We did meet with the key cast and crew before principle photography started. The meeting with the crew was to give them all the current information regarding the two weeks of shooting that we had scheduled. We reviewed the script for technical purposes, i.e. lighting, sound, power concerns, etc. The meetings with the cast took the form of rehearsals which we conducted for about two weeks prior to start of principle photography.

Leanna: Besides the cast, what does your crew usually consist of? As you probably do not have a grip truck, how is equipment gotten from location to location?

Kim: We use the personal vehicles of the cast and crew to transport actors who lack vehicles as well as equipment, food, etc. We were not able to afford to employ a grip truck.

Leanna: Kim, how is costuming handled on a project? Is it “everybody wear what you want to wear” or are the costumes actually cleaned and put back on the rack at the end of the day? Does the cast supply their own costuming, is it supplied to them, or do you have a wardrobe allowance for them?

Kim: We had a limited number of costumes which we prepared with the help of our makeup crew. However, for the most part each actor was responsible for providing the wardrobe for his/her own characters. We would review a number of outfits and make a determination on which item of clothing most captured the look for that character. My wife, Deborah (producer) and I also used our own wardrobes when we felt it was necessary.

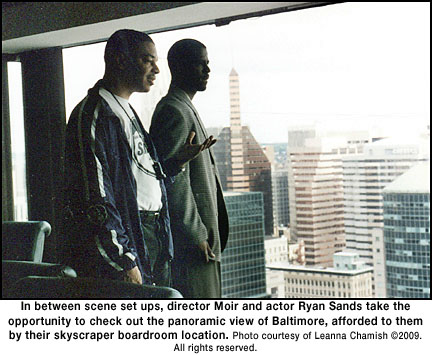

Leanna: You have worked both within sets and natural locations. What are the pros and cons of both?

Kim: Natural locations used the way we used them — without permits — carry a number of perils. However, when making films with no money, you’ve gotta do what you’ve gotta do. Location shooting is immediate. The actors tend to be more hyped given the lack of predictability with location shoots. They’re more open to mistakes such as dropping lines, missing marks, etc., due to the presence of onlookers or just the pressure of having to get a usable performance on tape before the arrival of authorities. Sound and lighting issues are frequently beyond our control and must be optimized. Using a set or a private home which we have permission to use tends to be a much less tense set — more laid back. We can control many more elements in a secured set/location which makes for a better in product/performance generally.

Leanna: You’re on the set, miles from civilization, and “nature calls”. When on remote locations, how have you handled bathroom facilities for cast and crew?

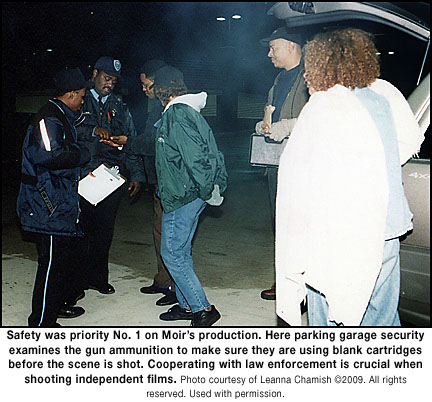

Kim: We’ve never been so far from bathroom facilities that we had to concern ourselves with that. We do location scouts for all the locations that we use, whether or not they’re secured or not. Sound, power and comfort issues are always addressed. The most difficult location we faced while shooting “Sinsitivity” was on the rooftop of a downtown garage which we did not have permission to shoot on. We did, however, scout out bathroom facilities within the garage before we arrived for the shoot. Despite a number of difficulties with that shoot including being interrupted by the garage’s armed security force, bathroom facilities were not a problem.

Leanna: What kind of food prep, or catering do you set up for the cast and crew on film days? What kind of food is available and prepared?

Kim: My wife was responsible for feeding the cast and crew for which she did an excellent job. We occasionally employed a caterer for shoots involving the larger cast size, but for the most part she cooked all the meals for the cast/crew. We fed the crew well for the most part — with full course meals of chicken, fish, or shrimp; vegetables, deserts and soda, juice or water. On most occasions, we had leftovers due to the large quantities that she prepared and I’m safe in saying that her meals were frequently the highlights of some very difficult work days.

Leanna: While you may have employed special effects artists and make-up artists in your films, have you ever used a make-up artist for the glamour of the actors and actresses, or is that up to the individual performer?

Kim: We tried to have makeup artists on site for each shoot day. There were days when we were unable to provide a makeup artist, but those days were few. We always informed the cast ahead of time and usually in writing of what kind of makeup/wardrobe resources we had on each specific shoot date.

Leanna: Kim, how do you choreograph you fights and stunts to where there is the maximum of action and minimum of danger to the performers? Do you use padding? Do you use mats and empty boxes for the more dangerous falls? Have you had any mishaps on the set?

Kim: The assistant director, who also had an extensive theatrical background was primarily in charge of blocking the limited number of stunts that we had in “Sinsitivity”. He instructed the actors in how they should move in these situations in very specific, step by step detail. His input was greatly appreciated.

Leanna: What is the correct and safest way to use a gun with blanks loaded in it on the set or location? Do the performers wear earplugs? Is there any padding involved? Should the local authorities be informed that blank gunshots will be going off at such and such a location? I remember when the police showed up in the garage! Maybe you want to talk about that!

Kim: For “Sinsitivity”, we had to use prop guns — which were in fact real guns. Ideally you should have a gun wrangler or firearms expert on set to handle all prop guns, to assure that they either unloaded or loaded with blanks and to instruct the cast and crew in the proper way to use them. I spoke with gun store owners about the proper way to use and load blanks before turning them over to the actors. We did use ear protection.

As far as notifying the local authorities — that’s interesting because for “Sinsitivity” we didn’t have permits to do anything. We couldn’t afford them. Subsequently we shot everything guerilla style, on the move and with an eye out for the police. During our only shootout in the film which was staged illegally on the roof of a privately owned downtown parking garage, we ran afoul of the armed private security police who were employed by the garage owners. I’m not sure if they knew right away that we were a film crew when they encountered us, or whether they initially thought they had happened upon some criminal activity. Obviously there was room there for an untimely mishaps or accident. I don’t advise staging these kinds of events without notifying the authorities or employing firearms experts to advise and handle all weapons on set, but given the financial realities of indie filmmakers, I understand how these kinds of things happen. In situations where there are no permits and no experts are on set I followed several common sense rules. Ear and eye protection for anyone shooting a weapon and no weapons were aimed at anyone for any reason. I even had an unmanned camera capture the action so that there would be no risk for the camera operator.

Leanna: You are doing an action sequence in your movie, with fake guns and whatever, and a squad of real law enforcement pulls up. What is the most appropriate way to deal with this so it does not become a serious situation and delay your shooting schedule?

Kim: You should level with the cops if they come upon you shooting with firearms. Keep in mind, “Sinsitivity” was produced prior to 9/11 and many of the things that we were able to pull off regarding our guerilla-styled film shoots might be more difficult, or even more dangerous in contemporary times.

Leanna: Knives, axes, machetes, etc. can be really dangerous if not used properly in films. Have you used fake cutlery in your movies, or what has been done on your films to get around that danger factor?

Kim: We used fake knives in the one scene were a knife was used, and even that knife — a plastic one painted silver had it’s blade covered with a thin layer of gaffer tape.

Leanna: While perhaps most of your actors and crew might be from your local area, how do you handle actors and actresses that have to come from out of state. Where are they put up after the day wraps?

Kim: We only faced that problem on one of the shoot dates and it happened that that actress had a relative who lived in the Baltimore area who she stayed with while working on the film.

Leanna: Due to the many different personalities that you can encounter from cast and crew, how do you handle any friction or situations that spring up from time to time?

Kim: We had a number of interesting situations on our set, most of which revolved around actors not showing up on set when they were supposed to. There were also some issues surrounding stunts and what kinds of things were to be allowed during love scenes. As far as the actors not showing up — when this happened without prior notice, we simply fired those actors and replaced them. As far as the stunts were concerned, our assistant director who had extensive experience in staging stunts and fights served as our consultant in those situations. We rehearsed those situations before arriving on site and then reviewed our practices before committing those performances to tape.

As far the love scenes were concerned, we sat down each actor involved and reviewed the script. We told them what we needed to get a believable scene in the can. We had to make some compromises over what was in the script, but I don’t think any of those compromises had a adverse effect on the final outcomes and performances.

Leanna: Have you dealt with nudity in your films? What is the proper conduct and the way to deal with this matter so everyone involved is comfortable, and you get the shots you need?

Kim: Because the movie is dealing with exotic dancers and the story contained several love scenes, we had to review the script with the actors before we finalized our casting to assure that they’d each be comfortable with what was going to be asked of them. Nudity initially was to be required of both the male and female leads. While nearly all of the scenes featuring the female lead dancing in the strip club required her to wear the wardrobe of the dancers — which obviously leaves little to the imagination — the female actors were rarely required to wear less that might be required on most beaches.

We also negotiated with the actors camera angles that would conceal parts of the body that they felt uncomfortable baring. We did this because we were trying to get the best possible outcome for the film. While I don’t think it affected the overall outcome of the film, I’ve come to the conclusion since then that I won’t make those compromises so readily in the future. I feel that an actor’s job is to act — and create a believable atmosphere for the audience. Anything that compromises that objective is not true to the audience, not true to the film and therefore undermines the overall intent of the film.

Leanna: How do you go about scheduling actors and crew members for the days they are needed? Do you have someone in charge of continuity, logging and such?

Kim: Because of the financial constraints of the film, we didn’t have enough people to specialize in that way. I did the scheduling of the actors and crew after doing a breakdown of the script.

Leanna: Kim, do you shoot just weekends for a feature, or have you had a scenario where everyone takes a week off to shoot the full week non-stop?

Kim: I took off two weeks initially just to clear my schedule to allow me to concentrate on the making of the movie, but my cast/crew are all working folks. Subsequently we usually shot in the evening and on weekends.

Leanna: What importance do you put on having a crew member documenting the behind-the-scenes making of the movie, as well as taking photos of the characters at the locations and sets you are using?

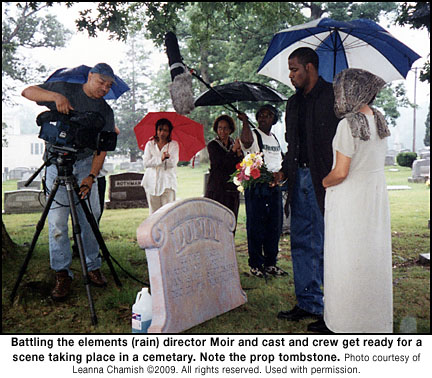

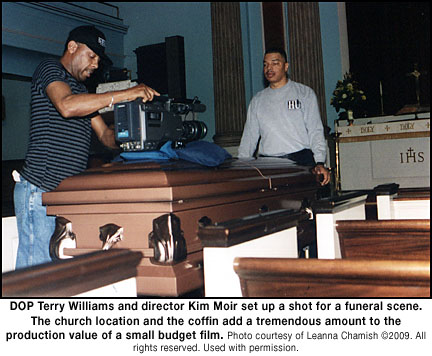

Kim: I thought it was important enough at the beginning of the project to give that responsibility to one of my most trusted crew members – you – Leanna. I’ve since come to find that I didn’t go far enough in photographing the action that happened in front of the camera between the actors that might have been used later in promoting the film. I found that covering the action both in front of and behind the camera is essential later on when time comes to promote the film to the audience, the media, potential investors, etc.

Leanna: Some filmmakers do everything they can to cover brand names of products in a movie, some blatantly don’t care if they show. What are the rules to product placement? Have you ever used any product placement in your features?

Kim: We had some limited experience with product placement — some of it unintentional. In those cases, the placement of a product or a company name was simply well placed within the scene because of a specific location. It would have been far too difficult to remove or cover up those names or products, so we just went with them. To the best of my knowledge, few manufacturers, companies, etc. have a problem with any kind of product placement that depicts the proper and intended use of their product. Problems can arise when using a product for something other that it’s intended use, or showing a product doing some kind of harm or in an unwise unflattering portrayal. We avoided those situations.

Leanna: Since everything is practically done on computers these days, can you tell me what software you edit your features with? Are you on a Macintosh or a PC? What do you feel is the bare minimum of hardware and software that you need to edit a feature?

Kim: We edited “Sinsitivity” on AVID Xpress for DV on a PC. We had a minimum of visual effects. One of the most involved was a chromakey scene showing two actors sitting in a car on a city street when it fact they were on a cover set posed in front of a blue screen. That kind of thing happens all the time on films of all varieties these days, but I don’t think it occurs often with films facing the kinds of financial constraints that we were faced with.

Leanna: What post production software do you use for your titles and 3D effects and other post production, outside of, or integrated with, the editing platform?

Kim: My editor used avid Xpress, Boris, Deko for titles and a number of other post-production software. The sound mix was done on a state of the art digital mixing console by a skilled sound re-recordist. Our film was not effects-heavy, so we didn’t have to do a lot of special things.

Leanna: With “Sinsitivity” and a lot of other production work under your belt, you have had to deal with many sound effects and soundtracks for these projects. How do obtain sound effects and music? Do you use stock music and sound effects libraries?

Kim: Sound effects was adeptly handled by my sound recordists Sounddave, Inc. A.S.C. They covered nearly all aspects of film sound whether or not it was location or studio, production or post-production. We made very limited use of sound effects libraries and used virtually no stock music.

Leanna: So for music, did you hire composers?

Kim: My editor, Ray “Thunder” Leftwich is also an accomplished musician. He composed a few pieces for the film. Otherwise, we worked with a variety of talented musicians who provided music to the production that complemented the images.

Leanna: Your film is in the can, it’s edited, and sound and special effects have been added. How do you go about finding a distributor? Do you have a favorite distributor that people should try first? Can you talk about what to look for in a distributor, and give any warnings about tricks to look out for, loopholes and catches that could hurt you, and so forth?

Kim: Film festivals are the place to go primarily when you’re trying to make contacts with distributors. You might also have some success by mailing out copies of your film to distributors, but my personal experience involved attending a film festival and making a contact at the festival that later materialized into a distribution deal. I don’t have a favorite distributor. I hate to sound like I have a negative attitude towards distributors, but they make far too much money to be, for the most part, non-creative middlemen. That’s my personal experience. Under the best of circumstances, a distributor should be a partner in the film to the extent that they profit reasonably by working hard to get the film to the marketplace — and the more successful they are with that job, the more they profit. That should also benefit the filmmaker as well, although it doesn’t always work out that way.

As far as advice for dealing with distributors, I would say that under no circumstances should you ever consummate a deal with a distributor without having an entertainment lawyer with some extensive experience in doing film contracts review the deal. You should keep a close eye on clauses in the film regarding cash advances, chargebacks or the cost of “delivering” the film to a distributor. A distributor can charge back everything that they do to promote your film unless the contract states otherwise. Issues such as percentages, errors and omissions insurance and the overall length of the contract to license the film are equally important. No distributor will take your film without errors and omissions insurance, commonly called E & O insurance. It covers the distributor should anyone attempt to sue them due to a defamation issue in the film; or if uncleared music used. It also protects the distributor and the artist on a variety of other legal issues. Make sure that you’re being adequately compensated for each revenue stream that you’re selling the licensing fee for, ie. cable TV, home video, etc. You should also make sure that you have legal rights to all of the music, locations, and performances in your film.

Leanna: So you recommend hiring an attorney familiar with contracts before you sign a distributor’s contract?

Kim: Without a doubt.

Leanna: Should you have a lawyer in general?

Kim:You may not need a lawyer until it comes time to talk $$. I’m not sure where a lawyer might be of benefit otherwise.

Leanna: What sort of contracts do you recommend that need to be used on an independent film? Are there any books or websites that you would point someone towards to learn more about these forms and how to obtain them?

Kim: The contracts that you should have are: deal memos with the cast and crew that give the filmmaker the rights to all work and performances and spell out each person’s financial compensation and participation. You should have a contract giving your permission to use each location shown in your film and spelling out what compensation is expected. You should have copyrights on all scripts, music rights and sync licenses for any music used in the film among others.

Leanna: Have you ever had to deal with insurance, location permits, or completion bonds on any of your movies?

Kim: We had an eye-opening experience with E & O insurance that before signing a distribution deal I had never heard of. The revelation was that it’s a very, very expensive item to provide and while I viewed it as the distributors cost of doing business, it’s not viewed that way throughout much of the industry.

Leanna: In this age of DVD competition, do you feel it is important to pack extras such as commentary, behind the scenes, and bloopers?

Kim: I feel that it’s essential to include those items. As a consumer of movies and DVD’s, I won’t generally purchase a movie that doesn’t offer something beyond the movie experience. That kind of DVD, I would just rent unless the film is so wonderful that I’m learning something from it on another level. I believe that the inclusion of extras is one of the many reasons that DVD has displaced VHS tapes.

Leanna: Kim, what kind of marketing materials should you have on hand to promote your feature?

Kim: Press kits with pictures of both the behind the scenes action and the action in front of the camera, bios of the cast/crew, 4×6 cards are the primary items used to promote a film. My most valuable promotional material for my film has been my website. It’s been invaluable in getting out the word on my film and it’s working 24 hours a day.

Leanna: Do you hold premieres of your movies or throw a wrap party at the end of filming?

Kim: I threw a premiere because I couldn’t afford to do a wrap party. It had to be something that would be self supporting at the very least and, ideally profitable.

Leanna: Are there any genres that you wish you were doing, but can’t because of money constraints (or the market isn’t there) and is there any genres that you refuse to touch, and for what reasons? Is budget a limitation?

Kim: I’ve got three scripts, a horror film, a romantic comedy set in Jamaica and a sci-fi/period piece that are currently beyond my ability to produce independently.

I’d like to produce the horror movie, but it’s got to be right in tone and texture. Some kind of “Eve’s Bayou” atmosphere – authentic. I’d also like to do a historical drama. I have a treatment for that ready to go and with films like “Troy” and “Alexander” being produced and succeeding it’s established the marketplace.

One thing that’s clear to me after producing “Sinsitivity” is the unavoidable nexus between $$$ and the ability to fully realize your vision on screen. We put every dollar of “Sinsitivity” on the screen and I got to experience that cause and effect.

Leanna: What genres do you enjoy working the most in?

Kim: Drama is my main interest because it’s meat and potatoes of the movies. It’s the genre in which many actors find their biggest challenge. It was a challenge for me to produce a drama that would be compelling.

Leanna: What is has been your best experience on a film? What has been your worst?

Kim: The entire film process was a great experience by and large. The worst experience in this case had to be shooting the love scene. It was a joy to visualize and write that scene, but the actual production of it turned out to be quite complicated. The actress had some issues about how much of her body would be on display in the scene, perhaps rightfully so. As much as I could I tried to convince her that I would never allow her to look bad in any way, but due to her perceived vulnerability it was a very challenging scene to get in the can. I think that in hindsight — after viewing the finished product, she’s happy with how it turned out.

Leanna: Is there anything else you would like to add to those who are trying to get into the independent film industry?

Kim: I would say that you should watch as many films and read as many scripts of the type that you’re interested in producing as possible. Learn from all films — good and bad because they all have something to teach you. Work hard at perfecting your craft — whether it be writing, shooting, lighting, acting, etc. Be the best you can be at the moment and always look for opportunities to improve. Be open to honest criticism and open to change. Be open to suggestions. I feel that one of reasons the set for “Sinsitivity” was so harmonious is that everyone from the makeup people to the actors knew that I valued their intellect. Subsequently, I listened to suggestions and implemented them where appropriate. I feel that I was secure enough in my skills as a director and my overall understanding of the story as the writer not to be threatened when others had ideas as to how to make “Sinsitivity” a better film. Everyone on the set also knew that I was the last word on what would be shot and respected my abilities. In many ways — it was the ideal learning experience.

Leanna: do you think that being African American presented any hurdles at any

stage of pre-production, production or distribution? Do you have any advice specific to African American filmmakers?

Kim: In this society, practically everything is more difficult to accomplish as an African American male. Obviously that’s not the popular line to take, but it’s real. There were hurdles to overcome being African American — examples being: renting equipment from vendors who are trained to view you suspiciously, securing locations from individuals who’ve been taught to fear you. Yet when it all came down to it, most of the people I dealt with dealt with were fair-minded, good people who dealt with me as an individual who was articulate, competent, professional and determined. It’s a testament to the overall goodness of people that this movie was produced. There were dozens of scenarios where it could have been sidetracked, but ultimately we got it done.

My advice to African American filmmakers would be to be hyper-competent, determined and professional in seeking opportunities in this business. Study the business and perfect your craft because there are those out there who will underestimate you and expect that you will present yourself before them without having done your homework. At that point, you’ve confirmed whatever stereotype they may have been harboring and they will dismiss you.

Secondly — tell your stories. There are tens of millions of them. There are so many stories of interest that spring from the African American experience. To do this, you must learn to write in an effective and compelling way. I’m sometimes dismayed by some of the half-baked, poorly written and conceived stories that find their way to the big screen or the video store. It seems that the more pathological, the more ignorant, the more low down, the more likely it is that those kinds of ideas will find their way to the production and distribution.

Leanna: What is your advice to anyone trying to get into the business as a director or producer?

Kim: Watch film, study it. Learn the language of imagery that we all speak and recognize on a conscious and unconscious level. Work at a production in any capacity that you can to increase your exposure and your skill sets.

If you want to write and produce your own work strong writing skills are essential.

Lastly — do it! You can talk about it, read about it, study it, but ultimately if you want to be a filmmaker, you must make films — shorts, features, docs — whatever, just do it!!

Special thanks to Leanna Chamish for contributing this great interview. Kim Moir is an incredibly talented filmmaker, and SINSITIVITY is a taut, well-done drama. Moir can be contacted at Bennuk@aol.com, and you can order your copy of the movie by clicking the image below.