Search

No Clowning Around: An In-depth Interview with

Director/Screenwriter Kevin Kangas,

Creator of the “Fear of Clowns” Franchise

Interview by Robert Long II (2004)

NOTE: At the time of the original interview, Kevin Kangas had just completed his second feature. It has been a few years since then and he has FEAR OF CLOWNS 2 under his belt and is in preproduction on his fourth movie. He has kindly updated a few things in the interview for me, but for the most part this will deal strictly with the first two films. In the future I hope to interview him again for an update on what has been happening since FEAR OF CLOWNS.

Robert: Kevin, congratulations with the success of HUNTING HUMANS. At the time of this writing your second feature, FEAR OF CLOWNS, is nearing completion. Now, on both movies you have used film (HH was 16mm, FOC was part super16/part mini-DV): what are the pros and cons of using it over video?

Kevin: Video still isn’t in a place where it can duplicate the look of film. Even the best video cameras (like the Hi-Def ones Lucas uses) still can’t completely match the color and contrast range that film can though they get closer all the time. Some of the other perks of film are that you can really only get true slow-motion from film cameras unless you get one of the really expensive video cameras, which are out of the low-budget filmmaker’s reach.

Robert: What kind of affordable film or video camera would you recommend to those in the independent film business? What are the pluses and features on these cameras?

Kevin: I think recommending things like that are a bad idea. If you’re so new to filmmaking that you don’t know much about the equipment, your best bet is one of two things: 1) Go buy any video camera you can afford and start shooting shorts so you get a feel for how things are done. Edit them into tight little shorts and show them around. Repeat multiple times and then move up to longer features. 2) Get yourself a director of photography (DP) who knows what he’s doing and get him to rent the package he’s comfortable with (or if you luck out like we did with “Hunting Humans” then the DP might come with his own package). A director of photography is one of the most important pieces of the puzzle in the creation of the movie, especially if you’re fairly new.

Robert: What kind of lighting equipment do you use? What do you feel is essential as a basic kit for someone starting out in this business?

Kevin: On my first movie, “Hunting Humans”, we didn’t have a light kit. We had a lowel DP (500 watts) and a softbox (1000 watts), plus some assorted scoops (which are just the little silver dishes with a lightbulb in the center that you can buy at the hardware store).

On “Fear of Clowns” we used a light kit that contained 4 assorted lights (A DP, a VP, a tota and an omni light), plus another DP and a softbox.

As important as having tons of lights is knowing how to use them. If you don’t know how to use the lights to create mood then the lights are worthless. There’s a reason they call it “painting with light”. Get a book on lighting for film and study it, then watch movies and try to figure out where the lights are.

Once you know how to light, rent or buy a light kit, or if you’re really strapped for cash build yourself one. Build yourself reflectors (My DP on FOC taught me a great new trick–go to the nearest Home Depot or Lowes and look for the giant 8 by 4 foot sheets of styrofoam–I think it’s for roofing. Cut it in half and put gaffers tape around the edges to keep it from shredding. You now have a great reflector because one side is white which will give you a nice soft bounce of light and the other side has foil which will give you a brighter, harsher glare. The sheet we bought cost like $10 and made two 5 by 4 foot reflectors)

Robert: Your last couple of movies have been with your partner Rick Ganz of Marauder Productions. What are pros and cons to this collaborative effort? What compromises have to be met to have a good creative team up?

Kevin: The pros are that two heads are almost always better than one. We can also do a lot more work than one person. The cons are that there will always be disagreements. As long as both partners understand their part you shouldn’t have a problem.

In the case of Rick and I, I ultimately have final say on just about everything. Since the screenplay is mine, ultimately the vision for the film will be mine so any big decision comes down to me. I tend to rely on Rick a little more when the acting comes into play, since he’s better at that. He helps coach some of the actors when they’re having a hard time.

He’s fine with that. Eventually he may move on to his own things and then he’ll have the final say, but for now I think he’s happy with the way things are going.

Robert: What kind of preplanning do you do for an upcoming film? Do you storyboard? Do you hold script meetings to get feedback on what will and will not work?

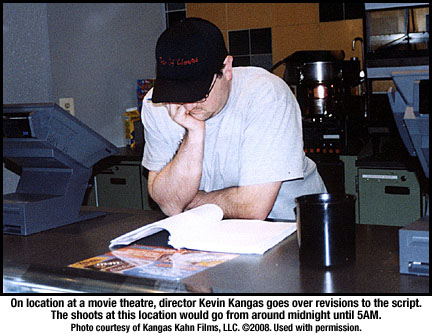

Kevin: Preparation is EVERYTHING. If you do not prepare for absolutely everything that you can then you will have a miserable time of things. You need to break the script down into a shooting script, you need to prepare call sheets with everything from which actors you need that day to which props/fx you need, you need to have a backup plan in case your outdoor shot gets rained on or your location becomes unavailable. There’s a million things you need to prepare for and you’ll still always get surprised by something.

But if you are well prepared then things will go easier and you won’t feel so overwhelmed. One of my main strengths on Hunting Humans was that even though we were winging a lot of it, I was very prepared, and I also improvise pretty well.

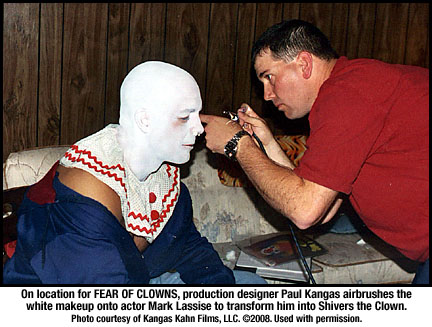

My brother (Paul C. Kangas), who designed the makeup of Shivers the Clown in FOC (and airbrushed him every time we needed him), did a few storyboards, but I don’t find I need them that much. When I write a shooting script I have a pretty solid idea of the shots in my head. If I did more complicated fight scenes or car chases then I’d probably storyboard a little more.

Robert: Are your films self-financed, or do you have investors? If you have investors, what is your advice on how to obtain them?

Kevin: Hunting Humans was mostly self-financed. I raised enough money on my own to shoot it, but once it was in the can it took us over eighteen months to raise the money to get it developed and transferred to video for editing. So it just sat at Fotokem (a lab in L.A.) for almost two years. I credit “Ernest Bay” as a coproducer on the movie, which was my nod to E-bay, since I sold a bunch of stuff there to pay for the movie. Toward the end of post-production one of our actors (Jeff Kipers) came onboard with completion funding so we could hire a composer and finish the movie.

FOC actually had investors. Jeff Kipers came onboard early since he was happy with the deal we got on Hunting Humans, and I also had money to put back in. Someone I knew for years (Joel Baker) mentioned to me that he invested in real estate but was looking to branch out, so I put together a little prospectus about what we were doing. We also shot some promo footage and I made a trailer to show what we intended. Everyone really liked the promo and the pics, and Joel offered to put in the final third of the budget.

Finding investors is, without question, a very hard thing to do. There’s no definite way of doing it. You probably know someone with money, whether it’s your doctor or your dentist or your lawyer. Bring them something professional (a prospectus is nice, and a trailer for the film you’d like to shoot is also a plus) and see if you can get them interested. Don’t bug them or be too persistent though. Desperation is a turn off. Put out feelers. Act like you don’t need them. Act like you’d be doing them a favor to let them invest. This is all a bit easier if you already have something done. No one was interested in us when we tried to do “Hunting Humans”, but on FOC it was pretty easy to raise the money.

Robert: What, of all your projects, has had the smallest budget?

Kevin: Hunting Humans had the smallest budget – $23,000.

Robert: Can you give me examples of where the money goes on a project? Can you give me cost reasons of why one film is more expensive than the other?

Kevin: On Hunting Humans most of the cost was involved in the film. We shot on barely a 2 to 1 shooting ratio. We shot a total of 5.5 hours of film to make it into a 90 minute film. Many of the shots in the movie were one-take only shots. As far as specifics, purchasing the film itself cost $135 per 400 foot can (approximately 12 minutes of film). We bought 28 cans so the cost of the film alone was $3780. Here’s a rough approximation of some of the other main costs:

$680 Transportation for DP/1st Assistant Cameraman (AC)

$1100 Lodging for DP/1st AC

$1600 3-weeks Food (normally called Craft Services, but we did our own)

$2000 development of film (approximately $.18 per foot)

$3500 transfer to video (approximately $300/per hour–not per hour of footage but per hour of their time – and this is only for a one-light transfer). Cost will vary depending on how nice you want your picture to look.

Including the cost of film, that’s almost $13,000 and you haven’t put anything on the screen yet. There’s prop costs, cost of editing equipment including blank tapes (our master wound up on BetaSP which costs about $25 per blank tape–nowadays we use Digibeta which is about $45 per blank two-hour tape). There are composer fees, actor fees (you can try to defer this, but some of them won’t do it without some money, especially actresses doing nudity).

Robert: Have you ever had to deal with insurance, location permits, or completion bonds on any of your movies?

Kevin: No. You always get whatever location releases that you can, but typically when you’re as low-budget as we have been, you can’t afford any of the above (and a completion bond is worthless unless you’re talking big money).

Robert: Is there script-writing or script-formating software out that you recommend using?

Kevin: Get comfortable with one and use it. I still use Scriptware (which is an out-of-date program that I’m comfortable with). I’ve used Final Draft which is fine, but they’re all pretty similar. It seems Final Draft is becoming the standard, so I’ve begun using it recently.

Robert: Who comes up with the story and the script? Is it a collaborative effort? Do you allow outside contributors to submit a story outline or synopsis?

Kevin: I have come up with both stories and scripts. We don’t accept unsolicited stuff because that leaves you open to lawsuits.

Once I’m done a script I pass it on to Rick and my brother for their comments. I revise it as much as possible given the timeline, and then we shoot.

Robert: What genres do you enjoy working the most in? Are there any genres that you wish you could work in but cannot because of budgets?

Kevin: Obviously I’m a big horror fan. That’s my main bag. If you looked at my top-ten movie list probably six of the ten are horror (some notables are Halloween, John Carpenter’s The Thing, Aliens, The Birds).

But I love a lot of stuff. I really enjoy Westerns and would kill to do one, but a lot of your money is tied up in costumes and making the sets look realistic. Couple that with the fact that Westerns don’t do that well anymore and it’s not a great bet. Still, if I had some money I’d do it because I love them.

I love fantasy and have written a fantasy script that also incorporates some horror elements. Like the Western, you’re now talking big money for sets and costumes, then you get to throw in FX costs too.

I love sci-fi too. Really, I enjoy a good movie, and every genre has good movies. The only genres of movie I’m not interested in directing are probably the straight drama and the romance. My interests don’t lie there right now. Probably not enough killing in either of those genres to keep my interest (sorry, mom).

Robert: How do you go about holding auditions for a new project? How do you get the word out? Where do you hold the auditions? Do you have any sort of form for the actors to initially fill out at the audition? Do you video tape the auditions? Do you allow actors to send in video taped auditions with their resumes?

Kevin: We typically advertise in Backstage magazine, which costs about $50 bucks but will get you anywhere from 500 to 1500 headshots. We also received a lot of headshots in emails, which was helpful because we can possibly eliminate them right away if they don’t fit any characters.

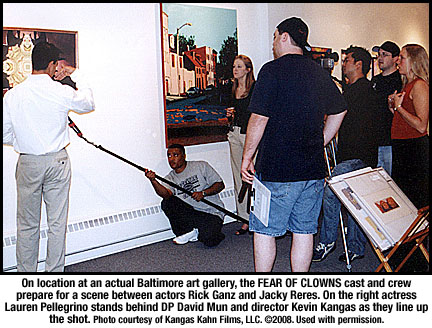

We held the auditions for FOC in a local hotel’s meeting room. We had about 200 people show up, and we videotaped the auditions so we could watch them later to see how they played on video. I also make notes while they are auditioning.

We also accepted auditions on video if they were out of state, but we let them know that if they were cast they would have to come to town, and we couldn’t afford to pay their travel or lodging(though we did pay for the lead actress’s lodging). We received about 80 taped auditions, and we had callbacks about a month later so we could re-audition the ones we thought had possibilities. If we’re interested we have people send a second audition tape. This was how we cast Lauren Pellegrino (an actress from New York) and a couple of others.

Robert: Do you feel it is important to get together with the cast and crew before shooting officially commences to go over the film, the plot, the duties of the individuals, and conduct and etiquette on the set?

Kevin: I think rehearsal is the most important reason to get together. That’s where you can clear up problems with line readings and motivations. If you feel like someone’s going to be a problem, then yes, you should probably pull them aside and explain to them what’s expected. But on the whole, I don’t think that point is necessary. You should have some detailed discussions with your DP so he knows what look and mood you’re going for, and so you know you’re speaking the same language (shot sizes are notoriously non-standard, so someone’s medium close-up may be someone’s close up–make sure you and the DP are on the same page)

Robert: What are the advantages and disadvantages of working with Union or non-Union actors?

Kevin: The advantages of non-Union are obviously that payment is optional. The disadvantage is that your talent pool may be thin on talent, and you’re going to have to work much harder to fill your roles with people who are good. You might, when you put your ad out, look for those who are Union-eligible. Essentially they have the credits to go Union, but haven’t yet because they know that will knock out their chances of working on non-Union movies.

The advantages of working Union are that you get a lot more talent to choose from. You may be able to get a familiar face in your movie (some TV star that people recognize but don’t know the name) and that can be the straw that tips the scale and gets you in that big festival.

The disadvantage of working Union is that even with the lower-budget agreements you have to pay the Unions upfront the entire projected salaries for all Union actors you’ll be using, along with a bond that I believe was around $20,000 at last check (NOTE: Check with your local SAG office and they’ll send you a complete kit about working with SAG). This bond ensures that if you run over the projected budget you will never be able to screw the actors because the Unions will pay them out of the bond money. So they will tie that bond money up for as long as they think necessary. Another hang-up with the Unions is all of the rules you need to follow. If you don’t follow the rules you’ll incur costly penalties that you probably don’t have the money for.

Robert: Besides the cast, what does your crew usually consist of?

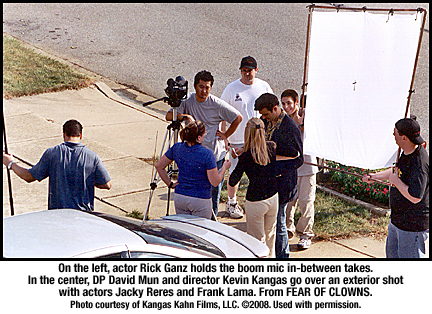

Kevin: On Hunting Humans the crew was myself, the DP, the first AC and whatever actors were in the scene. I typically handled the audio–a lot of the time we didn’t have a boom operator so we just put the mic as close to the actors as we could. On FOC we had me, the DP, a first AC, two sound guys (one to boom) and occasionally a few PA’s (Production Assistants).

Robert: As you probably do not have a grip truck, how is equipment gotten from location to location?

Kevin: We had a truck and anything that wouldn’t fit was put in another car, whoever was going to be at that location. Everyone pitched in to help unload and load.

Robert: How is costuming handled on a project? Is it “everybody wear what you want to wear” or are the costumes actually cleaned and put back on the rack at the end of the day? Does the cast supply their own costuming, is it supplied to them, or do you have a wardrobe allowance for them?

Kevin: It’s pretty close to wear what you want. I talk to the main characters and explain what kind of clothes that character would and wouldn’t wear. So Jacky, the lead actress, only brought stuff I told her the character might wear. In the case of the lead detective (played by Frank Lama)–I physically went to the store with Frank and bought him a suit and a couple of shirts that I thought the character would wear. Pretty much everything else was wear what you want. In the case of the police uniforms we had, those were put away at the end of the night in preparation for the next time they were needed.

Our wardrobe allowance was small, so whenever you can get away with having the actors wear their own clothes then it’s a good thing. The actors normally don’t have a problem because at least they know the clothes are going to fit–unlike some things out of wardrobe.

Robert: You have worked on natural locations. What are the pros and cons of it compared to a set?

Kevin: The only pro is that you normally don’t have to do a ton of production design. Either it looks okay to fit your needs or it doesn’t. So there isn’t a ton of decorating or changing. The cons are multiple. The biggest is sound. It’s very hard to control sound on location. For instance, on FOC we had a day we were shooting at a gallery in downtown Baltimore. We scheduled the shoot months in advance for a Sunday (when they were closed). Turns out there was a huge Columbus Day parade on that very street and they had closed it off. We had to drive our equipment truck the wrong way down a one-way street just to get to the gallery, and then we had to hold the entire shoot up for about 90 minutes while this parade (with lots of screaming people and banging drums) walked by.

Also, on location you can’t control the elements. Rain can postpone your shoot. Wind can play havoc (we had so much wind one day that we couldn’t use the steadicam because it would blow the camera off balance). Wind also screws with your sound.

For most low-budget filmmakers though, getting a set is impossible so it’s not worth consideration. You’re probably going to have to shoot on location, so prepare for it. Have a backup plan. Be ready to loop your audio in post if you can’t get good audio there. Always get good ambient (background) sound.

Robert: You’re on the set, miles from civilization, and “nature calls”. When on remote locations, how have you handled bathroom facilities for cast and crew?

Kevin: I haven’t had to deal with that. If I did I’d probably rent a port-a-potty. I think they’re only like $75 a day or something.

Robert: What kind of food prep, or catering do you set up for the cast and crew on film days? What kind of food is available and prepared?

Kevin: I looked into actual craft services but it was still pretty expensive, so my wife did most of the food prep. We had all sorts of sandwiches, some stuff for the people who were vegetarians. A couple of days we shot at my parents’ house and my mom fixed some beef stew. We had hamburgers one day. We vary it. We always had snacks and soda/water/juices available.

Robert: While you may have employed special effects artists and make-up artists in your films, have you ever used a make-up artist for the glamour of the actors and actresses, or is that up to the individual performer?

Kevin: Individual performer. On occasion we’ll touch them up with a little more foundation, but mostly we don’t worry about it. Call it realism, but I just don’t think everyone needs to look dolled up for every shot.

Robert: What is the best way, circumstances, and procedures to go about doing a “high speed car chase” for an independent film?

Kevin: Hire a stunt performer. If you try to do it yourself you’re bound to get in trouble. It’s one of the reasons I haven’t written one into any of my scripts. You need qualified professionals, you need insurance, and you probably are going to need a permit. All of those things cost more than your typical low-budget moviemaker can afford. If you’re hellbent to shoot it anyway, use telephoto lenses and drive fairly slow. The telephoto lens will make things look like they’re going faster by blurring the backgrounds. Intercut with a lot of close ups of the actors driving the car.

Robert: How do you choreograph your fights and stunts to where there is the maximum of action and minimum of danger to the performers? Do you use padding? Do you use mats and empty boxes for the more dangerous falls? Have you had any mishaps on the set?

Kevin: My brother and I (we’ve both taken martial arts training) get together and figure out some cool moves, some interesting hits. We practice it for a while until I have it down so I can show the actors who are involved.

For the fight scene at the end of Hunting Humans I took Bubby and Rick through the moves, and then it was just a changing it up a little once we were at the location. None of the fights are all that complicated in my movies (to do complicated fights requires actors who have martial arts training, or stunt doubles who do), so we didn’t really need any protective gear.

We’ve never had any mishaps, though there was a case in FOC where Rick got a little too rough. He’s supposed to dive into the back of Ted, who is pointing a gun at the lead actress. He came full force at a run and hit Ted pretty hard. Ted was surprised–not really hurt, though I’m sure he was sore the next morning–but that’s the take we used in the movie.

Robert: What is the correct and safest way to use a gun with blanks loaded in it on the set or location? Do the performers wear earplugs? Is there any padding involved? Should the local authorities be informed that blank gunshots will be going off at such and such a location?

Kevin: Someone on set needs to be experienced with guns. In our case, that’s me. We use two kinds of guns in my movie:

The first is a real gun with blanks. This kind of gun is used when the gun is pointed toward camera, so you can see the muzzle flash. For this kind of shot we back everyone away (even the DP is not behind the camera unless it’s a far-off shot done with a telephoto lens) and you can only shoot one blank at a time because blanks do not eject from a real gun (the compressed gasses in a bullet are actually what ejects them, so blanks do not pop themselves out).

This gun is the most dangerous to fire, because the blank will still fire paper and grains of gunpowder out the front at high speed (if you hold a piece of paper in front of the gun when you fire a blank, it will shred the paper). And if, in the case of Brandon Lee, there is something in the barrel when you fire a blank, it will be expelled out the front.

So I always check the barrel and load the blank myself. When the gun has been fired I move in and take the gun away and unload it.

The second gun is a blank-firing gun that has the barrel filled in, so nothing can possibly come out the front. This kind of gun will eject the blank shell because it has been built to. This is the kind of gun you’ll use for all shots when the gun is not pointed at the camera. You can safely put this gun up to your head and pull the trigger (I don’t recommend it though, because it’s VERY loud).

The performers can wear earplugs if they want. There is no padding used. I don’t advise you to contact the authorities unless you’ve paid for permits (if you have, then you will have let them know you will be shooting firearms and they will require you to have insurance and probably to have a police officer on set that day, all of which costs money)

Robert: You are doing an action sequence in your movie, with fake guns and whatever, and a squad of real law inforcement pulls up. What is the most appropriate way to deal with this so it does not become a serious situation and delay your shooting schedule?

Kevin: Well, I’d say you’re first move is to drop the weapons immediately before you get shot. If you’re lucky and you have a buddy who’s a cop, this is the day you’d like him to be on set wearing his badge in plain sight. He could go over and straighten this situation out.

But if you’re doing an action sequence involving guns in a public place, you almost have to notify the local authorities or you’re begging for trouble. If you’re in a small city they may actually send an officer out to supervise you for no charge.

If you notify the authorities and they ask whether you have a permit, say no and stress how low-budget you are. If they insist you have one, tell them you’ll work on it, then plan on having the gunfight on private property.

Robert: Knives, axes, machetes, etc. can be really dangerous if not used properly in films. Have you used fake cutlery in your movies, or what has been done on your films to get around that danger factor?

Kevin: Yes, we’ve used a lot of fake and real cutlery. In Hunting Humans the first scene where Rick attacks Catherine Granville in the shower–that was a nightmare. For the wide shot where Rick grabs her he had to have the real knife in his hand–when he jammed it forward he twisted it so it wasn’t near her.

On the close ups my brother had rigged a spring-loaded retractable look-alike. At least, it was supposed to be retractable. It turned out the spring was too tight so as we shot the close ups and Rick pushed the knife (the blade had been cut in half so the point was not sharp), the blade still managed to cut Catherine a little. She was a trooper though, and we did a number of takes.

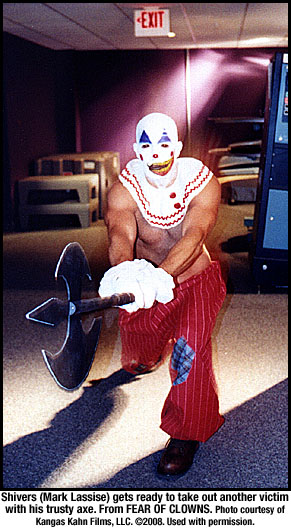

For FOC the clown has a big axe. For that my brother constructed a double of the axe made of wood. It looks very close to the original and really couldn’t hurt anything. So whenever you see Mark swinging the axe at a high speed it’s the stunt axe, and for the posed shots we used the real axe, which is called “the hero” for some reason.

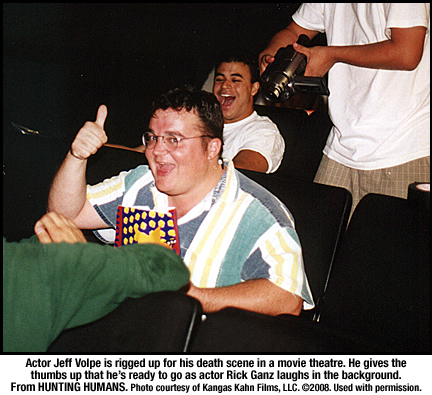

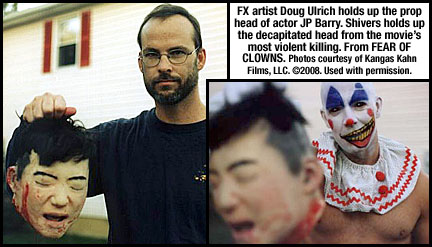

There’s a shot where Jeff Volpe gets an axe to the back of the head–Doug Ulrich, our FX guy, rigged a fake axe that was already embedded into a skull cap which we mounted on Jeff.

Another shot has the clown jamming the point of the axe into James Fellows’ back. For that Doug created a resin body cast with a pneumatic blade that would eject from the “chest” and appear to be the axe coming through.

So really, the proper way to use edged weapons is to not use real ones in any dangerous situations. Get yourself an FX guy who can make safe duplicates, or do it yourself. There are a lot of clever ways to stage shots so you don’t need to see the actual weapon connect.

Another trick I use is this: Show one or two well-shot deaths. As long as you deliver the goods there, the audience will give you leeway. If they see it once, they know what it looks like and it saves you time and money. That’s why the only guy you actually see get his throat cut in the infamous Hunting Humans movie theater scene is the first victim.

We didn’t have time to do the throat cut for every victim, so I figured if I showed it the first time, the audience would know that I COULD have shown it everytime and just assume that it’s a matter of artistic choice. We even had a few reviewers mention they were glad we stayed mostly away from the gore (and I apologize to them in advance for FOC).

Robert: While perhaps most of your actors and crew might be from your local area, how do you handle actors and actresses that have to come from out of state? Where are they put up after the day wraps?

Kevin: It depends. If their part is fairly small you try to schedule all their scenes in one day. As I said for our lead actress in FOC, Jacky Reres, we had her stay at a hotel close to us. When Lauren Pellegrino came into town from New York for two days of shooting, she stayed with Jacky since I had gotten a room with two beds.

Other than that we didn’t have any other out-of-towners that stayed overnight. If we did we would have gotten another room. Hotels are fairly cheap if you just need it for a couple of nights.

Robert: Due to the many different personalities that you can encounter from cast and crew, how do you handle any friction or situations that spring up from time to time?

Kevin: Address it immediately. Don’t berate or embarrass anyone in front of other people, but pull them aside if they haven’t already stormed off on their own. Normally it’s a simple misunderstanding. Try to present the other person’s point of view to the person, then do that with the other party. We haven’t had to deal with this much since everyone on FOC was a professional.

Robert: In your last couple of features, you have dealt with nudity on the set. What is the proper conduct and the way to deal with this matter so everyone involved is comfortable, and you get the shots you need?

Kevin: First and foremost you need a closed set. That means only necessary personnel are there when you’re shooting. For Lauren Pellegrino’s scene we had only the DP, myself and Lauren and Mark (the clown). You need to get a feel for how comfortable the actress is. If she’s very uncomfortable you just need to try to make her more comfortable. A good idea (and a way to stave off a possible lawsuit) is to have another woman on set making sure nothing happens that could be construed as sexual misconduct. She can also have a towel to cover up the actress in between takes.

Other than that, as long as you all act like professionals there should be no more difficulty than any other shot.

Robert: How do you go about scheduling actors and crew members for the days they are needed? Do you have someone in charge of continuity, logging and such?

Kevin: You should have a production manager who keeps track of when the actors are supposed to be on set. He should call the actors the night before their scene to remind them what time to be ready or on set.

For continuity you ought to have a script supervisor who keeps track of all that. We didn’t; we just couldn’t afford it. Shoot a lot of behind the scenes video which can help you keep track of what someone was wearing or what line they took a drink on. Use the video camera like a polaroid camera; take quick shots of people’s wardrobe on certain days. I actually asked my actors to make note of the outfits they wore during certain scenes so they’d know what they were wearing when we did subsequent scenes.

Robert: Do you shoot just weekends for a feature, or have you had a scenario where everyone takes a week off to shoot the full week non-stop?

Kevin: No, we shot both movies straight. Hunting Humans was 17 shooting days in a 21 day period. FOC was 18 shooting days over a 22 day period. People have to take off but it’s much easier to keep track of the story and shots. If you take a week off in between shoots you may get lost as to what’s been shot or you could lose momentum that’s building. On the other hand, you have a breather during the week if you only shoot weekends, so I can see how that would be appealing.

Robert: What importance do you put on having a crew member documenting the behind-the-scenes making of the movie, as well as taking photos of the characters at the locations and sets you are using?

Kevin: You definitely want someone behind the scenes shooting footage. The “Making Of”s are one of the most important extras on a DVD so you need that footage. Sometimes we didn’t have an extra hand so we didn’t get BTS (behind the scenes) footage on those. For Hunting Humans we rarely had BTS footage. On FOC we have some more, but there are still some scenes I wish we had shot some BTS stuff.

Robert: Some filmmakers do everything they can to cover brand names of products in a movie, some blatantly don’t care if they show. What are the rules to product placement? Have you ever used any product placement in your features?

Kevin: The rules are pretty grey here. What people try to do is simply cover themselves so the likelihood of being sued is minimized. Basically if there is something in the public domain in a public place, you really don’t need to cover it up.

However, if you have a killer kill someone using a Coca-Cola bottle and it’s pretty plain, you should reconsider. Coke could try to sue you for putting their product in a bad light. They would have to prove that you damaged their product, so they would probably lose in court, but do you want to fight that fight? They have billions to throw at lawyers, how much do you have?

So we try not to show too much copyrighted stuff and we’re careful that if we do show it we don’t make it too big on the screen. Fair Use laws are very vague, so just try not to call attention to any of that (and hey, I’m not a lawyer, so don’t take any of this as real legal advice).

Product placement is a whole different animal. Product placement is where the companies pay you (either with money or product) to show their product on screen. Most low-budget filmmakers won’t deal with this because companies figure whatever movie they’re making is too small to justify payment of any sort. We haven’t dealt with this though we may in the future now that we have made something of a name for ourselves. Hell, I’d put Milk Duds in my next movie if I could get a couple of free cases!

Robert: Since everything is practically done on computers these days, can you tell me what software you edit your features with? Are you on a Macintosh or a PC? What do you feel is the bare minimum of hardware and software that you need to edit a feature?

Kevin: I’ve edited both movies on a PC. HH was edited with Premiere 5.1 on an 800mhz PC using a Miro DC30Pro card. There were a lot of problems with this setup but it worked.

FOC is being edited on a 2.8mhz PC with the DVStorm2 card and Premiere 6.5, which is a much nicer setup. Great color correction, real-time effects, the works. I don’t know that there’s a minimum that you need to edit. When I edited HH on Premiere 5.1 with the Miro card I had a lot of people who looked at me funny and tried to tell me I couldn’t do it. They said Premiere wasn’t powerful enough; they said using IDE hard drives wasn’t fast enough. They were wrong on both counts.

Whatever editing system you put together, leave off any internet or virus checking software. That stuff will seriously slow down your computer. My editing system is separate from my internet machine. Any files I burn on CD and take to my editing system get checked for viruses first, then transferred.

Robert: With two films and counting, you have had to deal with several sound effects and soundtracks for these movies. How do you handle these subjects? Have you hired composers? Do you use stock music and sound effects libraries? What would you recommend to someone starting out?

Kevin: Yes, Evan Evans did all the music for Hunting Humans (and did a phenomenal job, btw). I licensed the music from him for the movie, which is what I’d recommend to any low-budget people. It’s normally cheaper, since the composer retains the rights and can further license the music out if he wishes. You just need to make sure you get the Master Use License and Syncronization Rights (two separate rights) for all music used.

We couldn’t use Evan for FOC due to his schedule but I found a great replacement in Chad Seiter, a very young but talented composer out of LA.

As far as pre-recorded music, you can license it but I don’t recommend it. It’s very hard to fit your picture to music that’s already licensed unless you’re just doing a music video or a montage.

As far as sound effects I typically create the ones I need. There are some good places to get them, which you can find on the web. Don’t buy those cheapie sound effect CDs you see in music stores; they’re typically not that great quality, plus they’re copyrighted so they don’t want you to use them (though the chances of them finding out about it and proving that you used one in your movie are very remote).

Robert: Your film is in the can, it’s edited, and sound and special effects have been added. How do you go about finding a distributor? Do you have a favorite distributor that people should try first?

Kevin: Your best bet is to submit it to small festivals and hope to win a few awards. Do a local showing to try to get some press. You want to get as much publicity for your movie as possible.

Then put together a press kit. This should be a nice folder with pictures and info about the cast/crew (anything that could be a selling point) plus production notes (tell interesting anecdotes about the shoot). Try not to talk about how you’re a genius and your movie will revolutionize the industry. I’m sure it’s true but it will make people dislike you.

Once you have that you can either submit to distributors (there are many books with their addresses–try the Hollywood Reporter’s Blu Book) or try to find a producer’s rep who will sell your movie to the distributors. I’d recommend the producer’s rep–that’s what we did with Hunting Humans. A producer’s rep can help you navigate the legal contracts that will be thrown your way–believe me, there are some shysters out there. You can find producer’s reps by punching that into any search engine.

Once you find one you’re thinking about using, research them. Contact people who have used them and find out how their experience was. If most of the people were happy with their experience, you’ve probably got a trustworthy rep. I used Integration Entertainment (www.int-ent.net) for FOC and found them to be very upfront and honest.

Robert: Do you recommend hiring an attorney familiar with contracts before you sign a distributor’s contract? Should you have a lawyer in general?

Kevin: Unless you’re a complete idiot you’d better have a lawyer on your side. He needs to be experienced in entertainment law also, not just the family lawyer, or the guy who got you out of the speeding ticket. This guy is going to cost some money (if he’s not your producer’s rep) but if you sign a contract with a distributor without a lawyer looking over that contract… well, you probably just gave your movie away.

Robert: What sort of contracts do you recommend that need to be used on an independent film? Are there any books or websites that you would point someone towards to learn more about these forms and how to obtain them?

Kevin: Look up Mark Litwak under Amazon and buy some of his books on legal contracts. That’s a good place to start. There are tons of web sites, just do a search on “actor release” and “location release” in any search engine. Those are the two big contracts you’ll need. Any more serious contracts and you need legal help. Harris Tulchin (www.medialawyer.com) has a disc full of movie contracts that costs about $90 and is well worth it. You can alter them to fit your needs.

Robert: What kind of marketing materials should you have on hand to promote your feature?

Kevin: The press kit. If you can come up with a poster for your movie that’s icing on the cake. A trailer for your film is also excellent. Anything you can do to help the distributor figure out how to sell your film is a plus. I had a great graphic artist named Erik Ashley do the posters for FOC. You can check out some of his stuff at www.unfaith.net, and even shoot him an email if you’d like him to design you one. His costs are very reasonable, especially for how professional he can make your poster look. As a bonus he’s also the leader of a band, so we licensed a couple of songs for FOC too.

Robert: Do you hold premieres of your movies or throw a wrap party at the end of filming?

Kevin: Yes to both. The wrap party is at the end of the shoot. It’s a great way to unwind with everybody and to say thanks.

The premiere is a good way to get publicity but it can get costly. We had our first premiere at a United Artists theater which cost about $800 for a Saturday morning show. We had a good turnout, but I wouldn’t advise doing it on Saturday mornings.

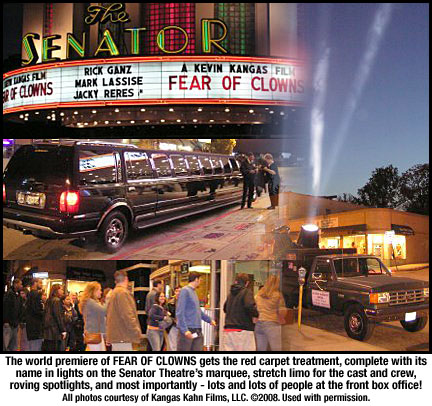

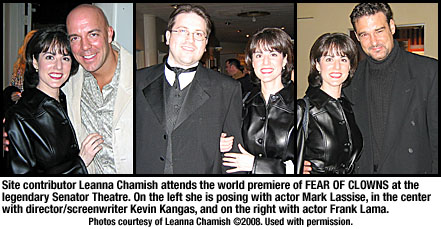

For FOC we did the premiere at the historic Senator in Baltimore, which was very expensive, but the spotlights and red carpet and names on the marquee made it a great night.

Robert: What is has been your best experience on a film? What has been your worst?

Kevin: Some of the magic of seeing what you’ve written take life on the screen is probably the best. Seeing “Hunting Humans” up on the big screen at the premiere was surreal, and really put a nail in the coffin of me ever doing anything else for a living. To see my movie up on a movie theater screen where I’ve seen so many of my favorite movies… wow.

Worst experience…there’s too many to name. The first day of shooting “Hunting Humans”–the experience is well documented on the “Making Of” that is on the DVD. Much of “Fear of Clowns” was a nightmare. If you’d like to know what shooting a low-budget movie is like, take a three week period and don’t sleep more than 4 hours a day. The other 20 hours do nothing but intensely physical and mental activities, and see how long you can function. But hey, you can take off three of those 21 days to refresh yourself. Before long, you too will probably be considering suicide. I’m not exaggerating. It’s that tough.

Robert: Is there anything else you would like to add to those who are trying to get into the independent film industry?

Kevin: Go find something else to do. Seriously. Unless you can’t NOT make movies, try something else. The road is incredibly hard, there are countless others trying to do it, and with the advance of technology that means there are umpteen wannabe hacks making movies, thinking they can make a quick buck. That means the distributors can be incredibly picky because there’s so much product out there. It also means that they have to wade through thousands of crappy videos, so yours will need to distinguish itself from them.

So if you’re saying “So what, I HAVE to make movies” then read on.

First, you need to read a lot. I mean, everything. Books, scripts, newspapers, magazines. You need to be incredibly well-read. Then you need to write. Write a lot. Your first couple of scripts are going to suck, but you won’t realize it. You’re going to think they’re very good but you’ll be wrong. Write more.

But wait…you just want to be a director. You’ll find a good writer and direct his script. You can do that. But there are a lot of obstacles in the way of being a director– 1) having to find a good script 2) secure the rights for next to nothing 3) battle the writer when you have to change his script because you can’t shoot something in it or you changed a little dialogue 4) There are a lot of extra forms to fill out when you register the movie and sell it to a distributor if you’re not the writer.

And hey, there are TONS of people who want to direct. Something not a lot of people realize is that to direct well isn’t that hard. If you have a support team behind you and a good director of photography it’s actually pretty easy. I’m not saying anyone can direct groundbreaking movies, but if you have a good script and a good DP, it would be very hard to NOT make a good movie, even with a novice director.

But writing…that is something that takes real talent. The writer is the only one who creates in a vacuum. He has to fill blank pages. Everyone else, including the director, depends on his instructions (the script). All of this is why writer/directors, on the whole, are much more respected and wanted in Hollywood than just directors.

Once you’ve gotten a couple of scripts under your belt and have shot some shorts, go for it. Gather talented people around you. That’s one of my little secrets. Surround yourself with talented people and you will turn out a better product everytime.

The more you shoot the better you’ll get.

Kevin Kangas

Kangas Kahn Films, LLC.

http://www.myspace.com/kangaskahnfilms

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm1292971/

Kevin Kangas has worked as a script reader at a prominent Los Angeles agency, and has written over twenty feature screenplays. He went to film school at the University of Maryland and has directed many shorts, as well as an award-winning training video for the national department store Hecht’s.

His first feature film, HUNTING HUMANS, won numerous awards and was distributed by MTI Home Video across the country. It was also picked up for foreign sales by IFM World Releasing, Inc.

FEAR OF CLOWNS, his second feature film, was distributed by Lionsgate Films in February of 2006. He is currently mastering the sound on the sequel, due out in late 2007.

(I would like to take this opportunity to thank Mr. Kangas for an extremely enlightening interview about the process of independent filmmaking. We of course wish his company much success on future projects. Information on all of his current features can be found on his website.)